- Home

- Kate DiCamillo

Beverly, Right Here Page 8

Beverly, Right Here Read online

Page 8

“Everybody loves to dance,” said Iola. “And this year, they are having a contest for the world’s largest turkey. They have had turkey giveaways before, but they’ve never had one where you could win the world’s largest turkey.”

“Can Elmer come over here for dinner?” said Beverly.

“Who?” said Iola.

“Elmer. My friend. The friend I made yesterday.”

“Elmer, your friend. Of course he can. When?”

“Today? Tonight? Now?”

“Yes,” said Iola. “Yes.” She smiled up at Beverly. Her wig was crooked. Her eyes were huge behind her glasses.

“I’ll just go and invite him, then,” said Beverly.

“Well, my goodness,” said Iola. “I guess I will get up out of this chair and start cooking. Tuna melts?”

“Tuna melts,” said Beverly.

She walked up to A1A. She walked past Mr. C’s, past the phone booth. She went up to Zoom City. She walked past the metal horse with his front legs stretched out as if he were going somewhere, when really he wasn’t going anywhere at all.

Elmer looked up when she walked in, and then he looked away.

“Do you like tuna melts?” she said.

Elmer didn’t say anything.

“Can you come over for dinner tonight?”

Elmer was silent.

“Okay,” said Beverly. “How about this one? What’s the square root of two?”

“When are you going to stop asking me questions?” said Elmer.

“I don’t know,” said Beverly. “Maybe when you start answering some. So. Can you come over for dinner tonight?”

He turned his head and looked at her. “No,” he said.

“Why not?”

“Don’t pity me,” he said.

“I don’t pity you.”

“Yeah? Well, did Jerome tell you what he used to call me?”

“Fudd,” said Beverly.

“Right, Fudd.”

“So what?” said Beverly.

“So th-th-that’s all, folks. I don’t need your pity. I don’t need to come to your house and eat tuna melts.”

“It’s not my house,” said Beverly. “It’s just where I’m staying. It’s a trailer, a pink trailer. It belongs to an old lady named Iola. She has a cat named Nod.”

Elmer shook his head.

“It’s close to the ocean,” said Beverly. “So it’s a crooked little trailer by a crooked little sea.”

Elmer smiled. He looked down at his hands.

“Come on,” said Beverly.

The door to Zoom City opened, and a man with a beard walked in. He was in his bare feet. He nodded to Elmer, and Elmer nodded back. The man walked over to the cooler.

From where she was standing, Beverly could see the horse outside — bolted into place, waiting.

“I don’t think so,” said Elmer.

“In a crooked little house by a crooked little sea,” said Beverly. “You wrote those words, didn’t you?”

“No,” he said. He shook his head. He looked up at her. “No, I told you I didn’t. Why do you keep thinking it was me?”

“Because I like the words so much,” she said. “Because they make sense to me.”

He smiled again.

“I’ll wait here,” she said. “It’s almost five. I’ll just wait outside for you. And then after dinner, I’ll drive you home. Iola has a Pontiac.”

“Gee!” said Elmer. “A Pontiac! And no, thank you. You’re not old enough to drive me anywhere.”

“I’m a great driver,” said Beverly. “I’ll wait for you outside. Okay?”

“Do whatever you want to do,” said Elmer.

Beverly was walking out of Zoom City when Mrs. Deely materialized out of nowhere and grabbed hold of her arm.

“I have good news for you,” said Mrs. Deely.

“Great,” said Beverly.

“I’ve produced a new installment, and I would like to share it with you.” Mrs. Deely was wearing the same duck-covered skirt she had on the day before, but today, there were three pencils shoved in the mountain of her hair, instead of just one.

“I’ve been called to draw the truth,” said Mrs. Deely.

“Yeah,” said Beverly. “You told me.”

Mrs. Deely handed Beverly a piece of paper. Beverly looked down at it and saw more snakes. And some lightning. And a lot of stick people dancing in the middle of a fire.

“Go on, take it,” said Mrs. Deely. “It’s for you. I must continue on. There are more people, young people, in need of the truth. It’s best to learn the truth when you are young.”

Mrs. Deely walked toward a kid who had just climbed on the horse.

“Halllloooooo,” Mrs. Deely called.

The kid was maybe four years old. His hair was shaved close to his head, and his mother was standing next to him. His mother said, “Isn’t this fun, Johnny? Isn’t this the most fun you have ever had?”

Beverly hated it when people told you how much fun you were having.

The horse started moving up and down in a resigned way.

“Isn’t it fun, Johnny?” said his mother.

The kid nodded. He didn’t seem all that convinced.

“I have the truth for you, Johnny,” said Mrs. Deely, walking over to the kid and holding out a paper.

Johnny looked at Mrs. Deely.

“Who are you?” said Johnny’s mother.

“I am the messenger,” said Mrs. Deely.

The door to Zoom City opened. Elmer stuck his head out. “Mrs. Deely!” he shouted. “Do not give him that paper!”

“But it’s the truth,” said Mrs. Deely. “And I am called upon to deliver it. I must deliver it.”

“Give it to me,” said Beverly.

“But you already have one,” said Mrs. Deely.

“I’ll give this one to a friend,” said Beverly.

“Really?” said Mrs. Deely. She smiled a radiant smile. “Thank you. Please do share it. That would be so wonderful.” She put out her hand and patted Johnny on the head.

“Stop that,” said the mother.

“Good-bye, Mrs. Deely,” said Elmer in a loud voice. “Thank you very much.”

He looked at Beverly.

She held herself very still.

“Fine,” he said. “You win.”

“Great,” she said.

“I’ll be out in a few minutes.”

“I’ll be here,” said Beverly. She folded up Mrs. Deely’s two pieces of paper and shoved them in her back pocket along with Mr. Denby’s happy family photo.

And then she stood and watched Johnny ride the horse.

He held on to the plastic reins and stared back at her.

“It’s so fun, Johnny,” said the mother. “Right?”

Right, thought Beverly.

Elmer came out of Zoom City with his book bag slung over his shoulder. “See what I’m talking about with Mrs. Deely?” he said. “What if the kid could read? It would scare the crap out of him.”

“That horse drives me crazy,” said Beverly.

“The horse makes kids happy, mostly,” said Elmer. “It’s Mrs. Deely who drives me crazy.”

They walked past the phone booth. It was glittering — shining in the hot sun. They both looked over at it at the same time.

“In a crooked little house,” said Elmer.

“By a crooked little sea,” said Beverly. She smiled a gigantic smile.

“What did you do to your tooth?” said Elmer.

“What?” said Beverly.

“Your front tooth is chipped.”

Beverly shrugged. “I was a kid.”

“And?”

“And I was running away from one of my mother’s boyfriends.”

Elmer nodded slowly. “Why?”

“Because he was chasing me.”

“Uh-huh,” said Elmer. “Why was he chasing you?”

“Because I had his wallet,” said Beverly.

“Oh,” said Elmer. “Right. Of cou

rse you did.”

The sun was beating down on them.

“I took his wallet, and he figured out that it was me who took it, and he chased me down the street yelling, ‘You worthless brat! Give me back my wallet!’ He was in his underwear, which made it pretty funny. And I was running as fast as I could, and then I tripped and fell on my face and chipped my tooth. After that, my mother stopped dating him. Or more like he stopped dating my mother. Because I was such a worthless little brat.”

“That stinks,” said Elmer.

“Right, well. I don’t care. I didn’t care.”

The cars roaring past them sounded like the ocean, or the ocean sounded like the cars. It was hard to tell the difference. A plane flew overhead trailing a banner that said EVERY HOUR IS HAPPY HOUR.

They both looked up.

“I will be so glad to get out of this place,” said Elmer.

“Yeah,” said Beverly. “Right. New Hampshire.”

“New Hampshire,” said Elmer.

“To get away from Jerome?”

“No,” said Elmer. “There are Jeromes everywhere you go. You can never get away from the Jeromes of the world.”

“Why didn’t you fight him? Why didn’t you fight back?”

Elmer shrugged.

“I would have beat the crap out of him,” said Beverly. “I’m thinking about beating the crap out of him right now.”

“Not everyone is you,” said Elmer. He moved his book bag to his other shoulder. “Not everyone eats glue and steals wallets.”

Beverly laughed. “This is it,” she said. She pointed at the trailer park sign. “We’re at the Seahorse Court.”

She led Elmer down the white driveway to the little pink trailer.

Iola was standing out front. “Howdy, howdy!” she called when she saw them. She walked toward Elmer with her hand out, smiling. “Now,” she said, “you are Beverly’s friend. You are Elmer.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Elmer. He took hold of her hand.

“I’m Iola Jenkins.”

“How do you do?” he said.

“I do just fine,” said Iola. “My goodness, you’re tall. Do you dance?”

“Not really,” said Elmer. “I mean I never have. I don’t know how.”

“How about I teach you?” said Iola. “There’s a dance tomorrow night at the VFW. The three of us could go.”

“Iola,” said Beverly.

“Shhhhh,” said Iola. “Let the boy make up his own mind.” She pulled the flyer out of her dress pocket and presented it to Elmer. “Ta-da,” she said.

“Christmas in July,” Elmer read. He looked at Iola. “But it’s August.”

“You just think about it,” said Iola. She patted his arm and took the flyer from him, folded it, and put it back in her pocket. “For now, come on inside, both of you. I made tuna melts. And peas.”

They went into the trailer. Beverly and Elmer sat down at the little table. Iola put a sandwich down in front of Elmer. “Thank you,” he said.

Iola came back to the table with a tuna melt for Beverly and one for herself. She gave everyone a scoop of peas. “Scooch over, darling,” she said to Beverly.

Iola sat down in the chair next to Beverly with an “oof.” She smiled across the table at Elmer. She said, “It’s usually just her and me at this table, just the two of us. And before she showed up, it was just me. But now, there’s three. Three of us. That’s good. I like it when the numbers go up instead of down, don’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Elmer.

Nod came walking through the kitchen, his tail held high.

“That’s Nod,” said Iola.

“Yeah,” said Elmer. “I heard about Nod.”

“Watch,” said Beverly.

Nod leaped up on top of the refrigerator and put his back to them. His tail started twitching. He stared at the wall.

“What’s he looking at?” said Elmer.

“He’s looking for a door,” said Beverly.

“A door to another world,” said Elmer.

“Right,” said Beverly. She couldn’t help it. She smiled at him.

“No, no,” said Iola. “There’s only this world. Besides, Nod ain’t going anywhere just yet.”

“How did he get the name Nod?” asked Elmer.

“Because of Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,” said Iola, “who sailed off in a wooden shoe.”

“‘But I shall name you the fishermen three: Wynken, Blynken, and Nod,’” said Elmer.

“Yes,” said Iola. “Just like that. Only there aren’t three anymore. There used to be a Wynken and a Blynken. Now there’s just a Nod. That’s how it is when you get old: you watch all the people and all the cats and all the dogs — and oh, just everything and everyone — you watch them all marching on past you, leaving without you.”

Yeah, thought Beverly, I get it.

Iola looked down at her hands, and then back up again. She said, “And that is why you go to dances every chance you get.”

“Will you stop about the dance?” said Beverly.

“I’ll go,” said Elmer.

“What?” said Beverly.

Elmer shrugged. “I’ll go,” he said again.

“We’ll all go,” said Iola. She clapped her hands together. “Goody.”

After dinner, they went out onto the porch and played cards. The crickets started up, competing with the sound of the ocean.

Beverly closed her eyes. The EVERY HOUR IS HAPPY HOUR banner flashed through her mind, and she heard Elmer saying that he couldn’t wait to leave. And even though the world was loud with living things, she suddenly felt lonely.

She opened her eyes. “Elmer’s leaving,” she said to Iola. “He’s going to Dartmouth.”

“Is that right?” said Iola. “Now, where is that?”

“New Hampshire,” said Elmer.

“He’s going to be an engineer,” said Beverly. “But he really likes art.”

Elmer shrugged. “I like to look at art. And I like to draw.” His face got red. “I’m not that good at it, but I like it.”

“Well, why don’t you paint me?” said Iola. She put down her cards. “I have always wanted someone to paint my picture.”

“I can’t really paint,” said Elmer. “I just draw — with a pencil, a charcoal pencil.”

“I know what,” said Iola. “You should draw a picture of me from when I wasn’t old. That’s what you should do. Wait right here.” She got up and left the porch and came back a minute later holding a silver frame with a black-and-white picture in it.

“That’s me,” she said, pointing at a tiny smiling woman. “On my wedding day. And that’s Tommy, my husband. That’s me,” she said again. “Can you believe it?”

Beverly looked at the young Iola smiling out of the photograph.

“You were beautiful,” she said.

“Pshaw,” said Iola. “I was happy is all. I loved Tommy, and he loved me. You know how I met him? We was in a play together. I was six years old, and he was seven. He was the sun, and I was the moon. Can you believe it? The sun and the moon. They raised us up high on ropes, way up above the stage. First the sun went up, and then it came down. That was Tommy. And then the moon rose up, and that was me. First came the sun, and then came the moon. I still remember my line: ‘Oh, world, I cast my dappled light upon you.’”

“What was Tommy’s line?” said Elmer.

“‘I shine the livelong day. I shine strong and brave and true,’” said Iola. “And that was the truth. He did. He was a good man. And a good dancer! Oh, he could dance. Everyone danced then.”

“Do you want me to draw you?” said Elmer. “I could do it right now.”

“You could?” said Iola. “Me now? Or me then?”

“Both,” said Elmer, “if you want.”

He got up off the couch and went and got his book bag. He pulled out a sketch pad and a pencil. “Sit next to the lamp,” he said to Iola. “And hold yourself as still as you can.”

Nod came in f

rom the kitchen, hopped into Beverly’s lap, and curled himself into a tight ball.

“Stupid cat,” said Beverly. She ran her hand over him — his small head and his bony back. Nod started to purr.

Elmer looked up at Iola, and then down at the paper, and then back up at Iola again. Moths flitted against the louvers of the porch, trying to get inside, closer to the light.

“I could draw you, too,” said Elmer, without looking at Beverly. “If you wanted.”

Nod purred louder.

“I don’t need anybody to draw me,” said Beverly.

“Oh, honey,” said Iola. “Don’t say that. It would be wonderful to have a picture of you.”

Elmer looked up from the sketch pad. He glanced at Beverly, and then he looked away.

He was smiling.

Beverly and Elmer walked down to the beach afterward.

They sat in the sand. Elmer sat close to her, his arm brushing up against hers.

“That made her happy,” said Beverly.

“Yeah, well,” said Elmer. “It’s not that great a drawing.”

“No,” said Beverly, “I mean all of it. Us being there.”

“Us?” said Elmer. He lay back. He put his arms behind his head.

“Us,” said Beverly. “You and me. Elmer and Beverly. Beverly and Elmer. However you want to say it.”

“The sun and the moon?”

“Right,” said Beverly. “Sure.”

She lay back in the sand, too.

There were stars in the sky — not a lot of them, but enough to convince you that there was something bright somewhere behind all of that darkness. And there was a moon, or a part of a moon, shining dimly.

“I have this friend who disappeared,” Beverly said, not sure why she was even saying it. “Her name is Louisiana Elefante, and she lived with her granny, and a few years ago, she and her granny just disappeared.”

“Disappeared?” said Elmer.

“Disappeared. Just gone, you know? We went looking for her. Me and this other friend, Raymie.”

For some reason, it felt strange to say Raymie’s name out loud.

She said it again. “Raymie.”

“Raymie,” repeated Elmer.

“Yeah, Raymie. She’s my best friend. Anyway, we went to the house where Louisiana and her grandmother lived, and it was empty. You could hear your voice echo. I mean, it was always empty — they didn’t have any furniture. But this was a different kind of empty. You could tell just by the way the house felt that they were gone, you know? It was terrible, walking through the house, looking and not finding anybody. I’ll never forget that feeling.”

The Tale of Despereaux

The Tale of Despereaux The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane

The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane The Magician's Elephant

The Magician's Elephant Raymie Nightingale

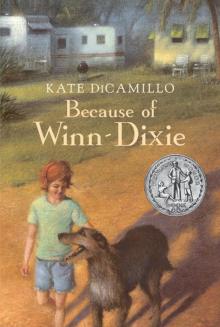

Raymie Nightingale Because of Winn-Dixie

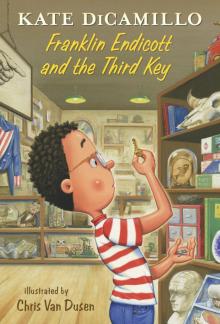

Because of Winn-Dixie Franklin Endicott and the Third Key

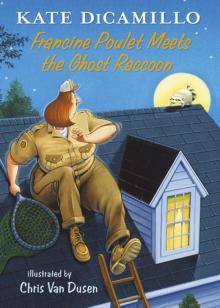

Franklin Endicott and the Third Key Francine Poulet Meets the Ghost Raccoon

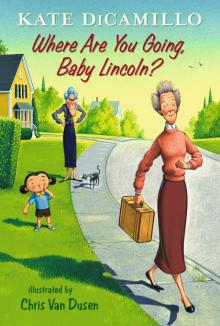

Francine Poulet Meets the Ghost Raccoon Where Are You Going, Baby Lincoln?

Where Are You Going, Baby Lincoln? Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures

Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures Beverly, Right Here

Beverly, Right Here Eugenia Lincoln and the Unexpected Package

Eugenia Lincoln and the Unexpected Package The Tiger Rising

The Tiger Rising The Beatryce Prophecy

The Beatryce Prophecy Leroy Ninker Saddles Up

Leroy Ninker Saddles Up