- Home

- Kate DiCamillo

The Tale of Despereaux

The Tale of Despereaux Read online

Also by Kate DiCamillo:

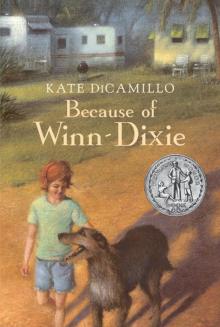

Because of Winn-Dixie

The Magician’s Elephant

The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane

The Tiger Rising

Mercy Watson to the Rescue

Mercy Watson Goes for a Ride

Mercy Watson Fights Crime

Mercy Watson: Princess in Disguise

Mercy Watson Thinks Like a Pig

Mercy Watson:

Something Wonky This Way Comes

Great Joy

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2003 by Kate DiCamillo

Cover and interior illustrations copyright © 2003 by Timothy Basil Ering

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.

First electronic edition 2009

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

DiCamillo, Kate.

The tale of Despereaux / Kate DiCamillo ; illustrated by Timothy Basil Ering. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: The adventures of Despereaux Tilling, a small mouse of unusual talents, the princess that he loves, the servant girl who longs to be a princess, and a devious rat determined to bring them all to ruin.

ISBN 978-0-7636-1722-6 (hardcover)

[1. Fairy tales. 2. Mice — Fiction] I. Ering, Timothy B., ill. II. Title.

PZ8.D525 Tal 2003

[Fic] — dc21 2002034760

ISBN 978-0-7636-2529-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-7636-4943-2 (electronic)

The illustrations for this book were done in pencil.

Candlewick Press

99 Dover Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

visit us at www.candlewick.com

For Luke, who asked for

the story of an unlikely hero

Contents

Book the First

A MOUSE IS BORN

Book the Second

CHIAROSCURO

Book the Third

GOR! THE TALE OF MIGGERY SOW

Book the Fourth

RECALLED TO THE LIGHT

Coda

The world is dark, and light is precious.

Come closer, dear reader.

You must trust me.

I am telling you a story.

THIS STORY BEGINS within the walls of a castle, with the birth of a mouse. A small mouse. The last mouse born to his parents and the only one of his litter to be born alive.

“Where are my babies?” said the exhausted mother when the ordeal was through. “Show to me my babies.”

The father mouse held the one small mouse up high.

“There is only this one,” he said. “The others are dead.”

“Mon Dieu, just the one mouse baby?”

“Just the one. Will you name him?”

“All of that work for nothing,” said the mother. She sighed. “It is so sad. It is such the disappointment.” She was a French mouse who had arrived at the castle long ago in the luggage of a visiting French diplomat. “Disappointment” was one of her favorite words. She used it often.

“Will you name him?” repeated the father.

“Will I name him? Will I name him? Of course, I will name him, but he will only die like the others. Oh, so sad. Oh, such the tragedy.”

The mouse mother held a handkerchief to her nose and then waved it in front of her face. She sniffed. “I will name him. Yes. I will name this mouse Despereaux, for all the sadness, for the many despairs in this place. Now, where is my mirror?”

Her husband handed her a small shard of mirror. The mouse mother, whose name was Antoinette, looked at her reflection and gasped aloud. “Toulèse,” she said to one of her sons, “get for me my makeup bag. My eyes are a fright.”

While Antoinette touched up her eye makeup, the mouse father put Despereaux down on a bed made of blanket scraps. The April sun, weak but determined, shone through a castle window and from there squeezed itself through a small hole in the wall and placed one golden finger on the little mouse.

The other, older mice children gathered around to stare at Despereaux.

“His ears are too big,” said his sister Merlot. “Those are the biggest ears I’ve ever seen.”

“Look,” said a brother named Furlough, “his eyes are open. Pa, his eyes are open. They shouldn’t be open.”

It is true. Despereaux’s eyes should not have been open. But they were. He was staring at the sun reflecting off his mother’s mirror. The light was shining onto the ceiling in an oval of brilliance, and he was smiling up at the sight.

“There’s something wrong with him,” said the father. “Leave him alone.”

Despereaux’s brothers and sisters stepped back, away from the new mouse.

“This is the last,” proclaimed Antoinette from her bed. “I will have no more mice babies. They are such the disappointment. They are hard on my beauty. They ruin, for me, my looks. This is the last one. No more.”

“The last one,” said the father. “And he’ll be dead soon. He can’t live. Not with his eyes open like that.”

But, reader, he did live.

This is his story.

DESPEREAUX TILLING LIVED.

But his existence was cause for much speculation in the mouse community.

“He’s the smallest mouse I’ve ever seen,” said his aunt Florence. “It’s ridiculous. No mouse has ever, ever been this small. Not even a Tilling.” She looked at Despereaux through narrowed eyes as if she expected him to disappear entirely. “No mouse,” she said again. “Ever.”

Despereaux, his tail wrapped around his feet, stared back at her.

“Those are some big ears he’s got, too,” observed his uncle Alfred. “They look more like donkey ears, if you ask me.”

“They are obscenely large ears,” said Aunt Florence.

Despereaux wiggled his ears.

His aunt Florence gasped.

“They say he was born with his eyes open,” whispered Uncle Alfred.

Despereaux stared hard at his uncle.

“Impossible,” said Aunt Florence. “No mouse, no matter how small or obscenely large-eared, is ever born with his eyes open. It simply isn’t done.”

“His pa, Lester, says he’s not well,” said Uncle Alfred.

Despereaux sneezed.

He said nothing in defense of himself. How could he? Everything his aunt and uncle said was true. He was ridiculously small. His ears were obscenely large. He had been born with his eyes open. And he was sickly. He coughed and sneezed so often that he carried a handkerchief in one paw at all times. He ran temperatures. He fainted at loud noises. Most alarming of all, he showed no interest in the things a mouse should show interest in.

He did not think constantly of food. He was not intent on tracking down every crumb. While his larger, older siblings ate, Despereaux stood with his head cocked to one side, holding very still.

“Do you hear that sweet, sweet sound?” he said.

“I hear the sound of cake crumbs falling out of people’s mouths and hitting the floor,” said his brother Toulèse. “That’s what I hear.”

“No . . .,” said Despereaux. “It’s something else. It sounds like . . . um . . . honey.”

“You might have big ears,” said Toulèse, “but they’re not attached right to your brain. You don’t hear honey. You smell honey. When there’s honey to smell. Which ther

e isn’t.”

“Son!” barked Despereaux’s father. “Snap to it. Get your head out of the clouds and hunt for crumbs.”

“Please,” said his mother, “look for the crumbs. Eat them to make your mama happy. You are such the skinny mouse. You are a disappointment to your mama.”

“Sorry,” said Despereaux. He lowered his head and sniffed the castle floor.

But, reader, he was not smelling.

He was listening, with his big ears, to the sweet sound that no other mouse seemed to hear.

DESPEREAUX’S SIBLINGS tried to educate him in the ways of being a mouse. His brother Furlough took him on a tour of the castle to demonstrate the art of scurrying.

“Move side to side,” instructed Furlough, scrabbling across the waxed castle floor. “Look over your shoulder all the time, first to the right, then to the left. Don’t stop for anything.”

But Despereaux wasn’t listening to Furlough. He was staring at the light pouring in through the stained-glass windows of the castle. He stood on his hind legs and held his handkerchief over his heart and stared up, up, up into the brilliant light.

“Furlough,” he said, “what is this thing? What are all these colors? Are we in heaven?”

“Cripes!” shouted Furlough from a far corner. “Don’t stand there in the middle of the floor talking about heaven. Move! You’re a mouse, not a man. You’ve got to scurry.”

“What?” said Despereaux, still staring at the light.

But Furlough was gone.

He had, like a good mouse, disappeared into a hole in the molding.

Despereaux’s sister Merlot took him into the castle library, where light came streaming in through tall, high windows and landed on the floor in bright yellow patches.

“Here,” said Merlot, “follow me, small brother, and I will instruct you on the fine points of how to nibble paper.”

Merlot scurried up a chair and from there hopped onto a table on which there sat a huge, open book.

“This way, small brother,” she said as she crawled onto the pages of the book.

And Despereaux followed her from the chair, to the table, to the page.

“Now then,” said Merlot. “This glue, here, is tasty, and the paper edges are crunchy and yummy, like so.” She nibbled the edge of a page and then looked over at Despereaux.

“You try,” she said. “First a bite of some glue and then follow it with a crunch of the paper. And these squiggles. They are very tasty.”

Despereaux looked down at the book, and something remarkable happened. The marks on the pages, the “squiggles” as Merlot referred to them, arranged themselves into shapes. The shapes arranged themselves into words, and the words spelled out a delicious and wonderful phrase: Once upon a time.

“ ‘Once upon a time,’ ” whispered Despereaux.

“What?” said Merlot.

“Nothing.”

“Eat,” said Merlot.

“I couldn’t possibly,” said Despereaux, backing away from the book.

“Why?”

“Um,” said Despereaux. “It would ruin the story.”

“The story? What story?” Merlot stared at him. A piece of paper trembled at the end of one of her indignant whiskers. “It’s just like Pa said when you were born. Something is not right with you.” She turned and scurried from the library to tell her parents about this latest disappointment.

Despereaux waited until she was gone, and then he reached out and, with one paw, touched the lovely words. Once upon a time.

He shivered. He sneezed. He blew his nose into his handkerchief.

“ ‘Once upon a time,’ ” he said aloud, relishing the sound. And then, tracing each word with his paw, he read the story of a beautiful princess and the brave knight who serves and honors her.

Despereaux did not know it, but he would need, very soon, to be brave himself.

Have I mentioned that beneath the castle there was a dungeon? In the dungeon, there were rats. Large rats. Mean rats.

Despereaux was destined to meet those rats.

Reader, you must know that an interesting fate (sometimes involving rats, sometimes not) awaits almost everyone, mouse or man, who does not conform.

DESPEREAUX’S BROTHERS AND SISTERS soon abandoned the thankless task of trying to educate him in the ways of being a mouse.

And so Despereaux was free.

He spent his days as he wanted: He wandered through the rooms of the castle, staring dreamily at the light streaming in through the stained-glass windows. He went to the library and read over and over again the story of the fair maiden and the knight who rescued her. And he discovered, finally, the source of the honey-sweet sound.

The sound was music.

The sound was King Phillip playing his guitar and singing to his daughter, the Princess Pea, every night before she fell asleep.

Hidden in a hole in the wall of the princess’s bedroom, the mouse listened with all his heart. The sound of the king’s music made Despereaux’s soul grow large and light inside of him.

“Oh,” he said, “it sounds like heaven. It smells like honey.”

He stuck his left ear out of the hole in the wall so that he could hear the music better, and then he stuck his right ear out so that he could hear better still. And it wasn’t too long before one of his paws followed his head and then another paw, and then, without any real planning on Despereaux’s part, the whole of him was on display, all in an effort to get closer to the music.

Now, while Despereaux did not indulge in many of the normal behaviors of mice, he did adhere to one of the most basic and elemental of all mice rules: Do not ever, under any circumstances, reveal yourself to humans.

But . . . the music, the music. The music made him lose his head and act against the few small mouse instincts he was in possession of, and because of this he revealed himself; and in no time at all, he was spied by the sharp-eyed Princess Pea.

“Oh, Papa,” she said, “look, a mouse.”

The king stopped singing. He squinted. The king was nearsighted; that is, anything that was not right in front of his eyes was very difficult for him to see.

“Where?” said the king.

“There,” said the Princess Pea. She pointed.

“That, my dear Pea, is a bug, not a mouse. It is much too small to be a mouse.”

“No, no, it’s a mouse.”

“A bug,” said the king, who liked to be right.

“A mouse,” said the Pea, who knew that she was right.

As for Despereaux, he was beginning to realize that he had made a very grave error. He trembled. He shook. He sneezed. He considered fainting.

“He’s frightened,” said the Pea. “Look, he’s so afraid he’s shaking. I think he was listening to the music. Play something, Papa.”

“A king play music for a bug?” King Phillip wrinkled his forehead. “Is that proper, do you think? Wouldn’t that make this into some kind of topsy-turvy, wrong-headed world if a king played music for a bug?”

“Papa, I told you, he’s a mouse,” said the Pea. “Please?”

“Oh, well, if it will make you happy, I, the king, will play music for a bug.”

“A mouse,” corrected the Pea.

The king adjusted his heavy gold crown. He cleared his throat. He strummed the guitar and started to sing a song about stardust. The song was as sweet as light shining through stained-glass windows, as captivating as the story in a book.

Despereaux forgot all his fear. He only wanted to hear the music.

He crept closer and then closer still, until, reader, he was sitting right at the foot of the king.

THE PRINCESS PEA looked down at Despereaux. She smiled at him. And while her father played another song, a song about the deep purple falling over sleepy garden walls, the princess reached out and touched the top of the mouse’s head.

Despereaux stared up at her in wonder. The Pea, he decided, looked just like the picture of the fair maiden in the book in the library. T

he princess smiled at Despereaux again, and this time, Despereaux smiled back. And then, something incredible happened: The mouse fell in love.

Reader, you may ask this question; in fact, you must ask this question: Is it ridiculous for a very small, sickly, big-eared mouse to fall in love with a beautiful human princess named Pea?

The answer is . . . yes. Of course, it’s ridiculous.

Love is ridiculous.

But love is also wonderful. And powerful. And Despereaux’s love for the Princess Pea would prove, in time, to be all of these things: powerful, wonderful, and ridiculous.

“You’re so sweet,” said the princess to Despereaux. “You’re so tiny.”

As Despereaux looked up at her adoringly, Furlough happened to scurry past the princess’s room, moving his head left to right, right to left, back and forth.

“Cripes!” said Furlough. He stopped. He stared into the princess’s room. His whiskers became as tight as bowstrings.

What Furlough saw was Despereaux Tilling sitting at the foot of the king. What Furlough saw was the princess touching the top of his brother’s head.

“Cripes!” shouted Furlough again. “Oh, cripes! He’s nuts! He’s a goner!”

And, executing a classic scurry, Furlough went off to tell his father, Lester Tilling, the terrible, unbelievable news of what he had just seen.

“HE CANNOT, he simply cannot be my son,” Lester said. He clutched his whiskers with his front paws and shook his head from side to side in despair.

“Of course he is your son,” said Antoinette. “What do you mean he is not your son? This is a ridiculous statement. Why must you always make the ridiculous statements?”

“You,” said Lester. “This is your fault. The French blood in him has made him crazy.”

“C’est moi?” said Antoinette. “C’est moi? Why must it always be I who takes the blame? If your son is such the disappointment, it is as much your fault as mine.”

“Something must be done,” said Lester. He pulled on a whisker so hard that it came loose. He waved the whisker over his head. He pointed it at his wife. “He will be the end of us all,” he shouted, “sitting at the foot of a human king. Unbelievable! Unthinkable!”

The Tale of Despereaux

The Tale of Despereaux The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane

The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane The Magician's Elephant

The Magician's Elephant Raymie Nightingale

Raymie Nightingale Because of Winn-Dixie

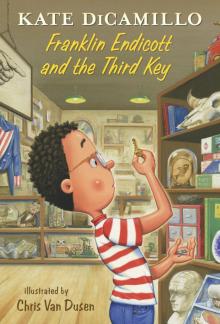

Because of Winn-Dixie Franklin Endicott and the Third Key

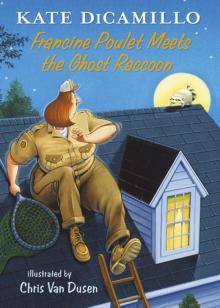

Franklin Endicott and the Third Key Francine Poulet Meets the Ghost Raccoon

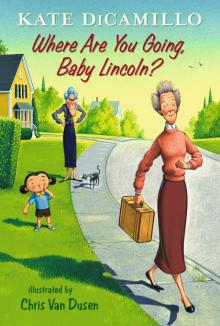

Francine Poulet Meets the Ghost Raccoon Where Are You Going, Baby Lincoln?

Where Are You Going, Baby Lincoln? Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures

Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures Beverly, Right Here

Beverly, Right Here Eugenia Lincoln and the Unexpected Package

Eugenia Lincoln and the Unexpected Package The Tiger Rising

The Tiger Rising The Beatryce Prophecy

The Beatryce Prophecy Leroy Ninker Saddles Up

Leroy Ninker Saddles Up